Nudging and its Impact on User Registration and Completion

What is a Nudge

In their seminal work “Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness” (2008), Thaler and Sunstein present how the use of appropriate nudges can produce enhanced outcomes, either for good or bad. Thaler and Sunstein define a nudge as: “… any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentive,” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

The following review will outline the different types of nudges and explain how they can be utilized to enhance the participation of insured individuals on digital platforms, ultimately achieving higher engagement rates and better outcomes (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

There are four distinct types of nudges. They are defined as:

Reflective-Decisive (RD) Nudges: These interventions target reflective thought processes, leveraging features that engage the automatic cognitive system. The specific nudging elements are central to the product selection decision (Anders Haug, 2014).

Reflective-Non-Decisive (RND) Nudges: These also aim to influence reflective thinking through the automatic system; however, the nudging elements themselves are not pivotal in the decision to choose the product (Anders Haug, 2014).

Non-Reflective-Decisive (NRD) Nudges: These focus on shaping behavior driven by automatic, non-reflective thinking. In this case, the nudging features play a critical role in the user’s product choice, even though reflective thinking is largely absent (Anders Haug, 2014).

Non-Reflective-Non-Decisive (NRND) Nudges: These influence automatic behavior without engaging reflective thought, with the nudging features not being essential in determining product selection (Anders Haug, 2014).

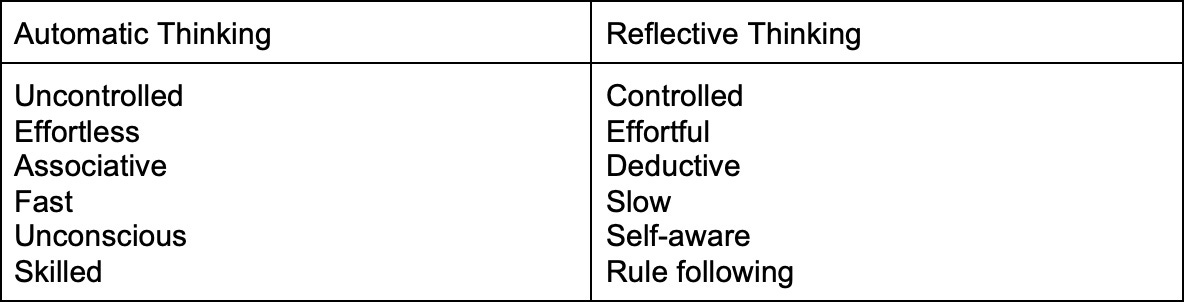

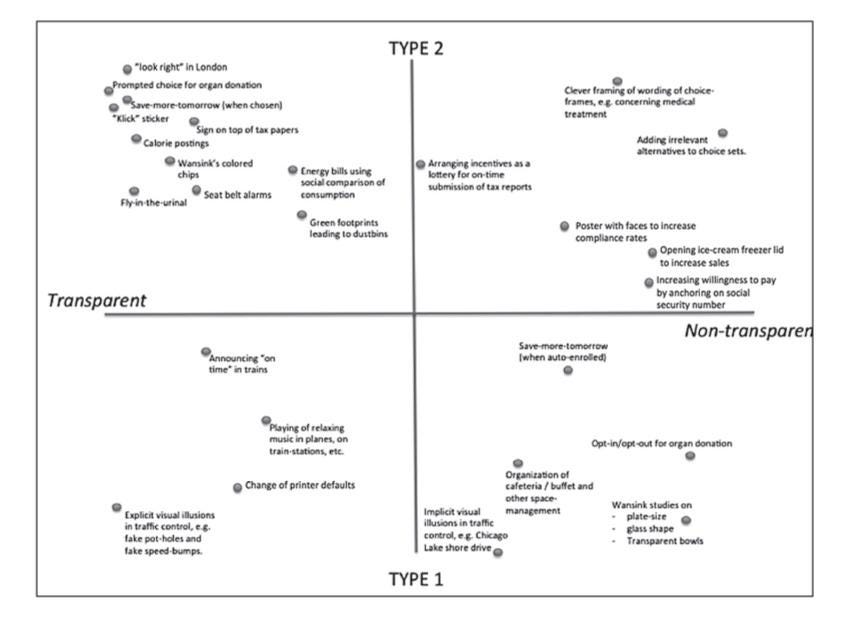

While Haug defined the two main types as reflective and non-reflective, Hansen and Jespersen used the terms Type 1 and Type 2 (Hansen & Jespersen, 2013). A Type 1 nudge is equivalent to non-reflective and is defined as a choice made with the automatic system; hence, you decide because you have always done it that way. A Type 2 nudge is performed with the reflective mind, which causes a pause in the decision-making process and prompts a person to reflect on their decision (Hansen & Jespersen, 2013).

The additional translation from decisive to non-decisive, transparent to non-transparent, is as follows: Decisive is considered transparent, which means that the decision was made while having the option to not make a decision. For example, the ubiquitous seatbelt alarm; you are fully aware of the alarm, and it is very transparent what the car makers want you to do. As a user, you can choose to ignore the alarm and not put on your seatbelt. Non-decisive is equivalent to non-transparent. It is best explained by Wansink’s studies, which changed participants’ plate sizes to reduce the number of calories consumed (Hansen & Jespersen, 2013). The user is only given one choice of plate size which they automatically pick up when entering the cafeteria, making the decision non-reflective and non-decisive (Type 1), as the user had no idea the plate was changed or even the existence of other plate sizes.

The chart below is a summary of the differences between automatic and reflective thinking.

Figure 1, Hansen & Jespersen, 2013

Understanding the adjectives used to differentiate the thought process will help one understand that nudging can be accomplished ethically once a choice architect decides on what outcomes are needed.

Below is a chart of the four different nudges, along with associated tests that categorize them.

Figure 2 (Hansen & Jespersen, 2013)

In conclusion, nudging is a viable method for identifying and achieving better outcomes for users and organizations. Understanding nudging will provide different methods of choosing call-to-actions and encouraging users to comply with simple requests, such as registrations, beyond simply asking politely.

Related Outcomes

In Drouin’s (2020) health-related study on using nudges with adults and children to help reduce childhood obesity and teenage smoking, he concluded that adults did not have a bias against using nudges to increase the likelihood of better outcomes for both adults and children (Drouin, 2023). The study has a similar makeup to the overall population of the current health insurance marketplace, where those who are privately insured are in the range of 18 to 66 years of age, for an average age 39.9 years old. Gender is not as consistent with the private health insurance carriers, where the study had 68% female, while insurance providers are closer to 50% each traditional gender. While there were other features, such as political leaning, these are not provided by the health insurance carriers (Drouin, 2023).

The importance of Drouin’s (2020) health-related study provides the basis for allowing a nudge, which will convince the user to register for a portal. What still needs to be determined is the type of nudge that will produce the best results.

Which Nudge?

As stated in Abdukadirov (2016), Jawbone, a device and mobile application, used a randomized controlled trial, a key method in behavioral research. Jawbone tested a subtle intervention in its mobile app, which supported its sleep and activity tracker. The app displayed a short prompt asking users if they intended to go to bed earlier. This gentle nudge, aimed at reinforcing commitment and consistency, led to a 72% increase in the likelihood that users would get at least seven hours of sleep (Abdukadirov, 2016).

While the Jawbone example is not an exact comparison, the results should provide a high standard for an appropriately designed nudge. The design should be close to a non-reflective-decisive nudge, meaning the user should want to enter the portal naturally, and then be decisive in choosing to complete registration. Like Jawbone, the user had a product. In our case, the product is health insurance, where the user made a decisive decision to purchase or acquire insurance through an employer. The next step is to determine how to integrate the product and portal to work together. Unless the current purchasing process is adapted to a more non-transparent process, in which the user is automatically enrolled, other alternatives should be considered. These nudges would have to be non-transparent because they will require the user to act with thought, and may include messages such as, “Your co-workers have signed up, don’t be the only one left,” or “Your group is getting close to complete registration.” Using these non-transparent nudges, the number of registrations will increase. The current insurance product to portal registration is 6.35%, meaning even a 10% increase will easily double the current registered population and provide better outcomes for the insurance carrier and its providers.

Related to Health Insurance

Dellaert et al. (2024) studied health insurance selection and found that using the appropriate amount of nudges directly affects the outcome of registering for a portal.

While this study performs three experiments, which use different models to determine the placement of plan options with users, the direct impact of the study is as follows:

“Our research also makes explicit another idea long implicit in the choice architecture literature: the idea of a user model. If choice architects have access to high-quality user models (i.e., accurate prediction algorithms), they can intervene more effectively because they can identify more precisely what is the correct option for each consumer,” (Dellaert et al., 2024).

Understanding the type of nudge required for the best outcome, and the ability to look beyond any A/B testing, is essential to increasing portal registration. Choice architects must understand that a user community is a grouping of groups, and that it is necessary to understand what can, with a high degree of probability, provide a nudge to users based on highly specific demographic and psychographic information.

Conclusion

The above description and cases of nudge theory shift the focus from behavioral outcomes to the features within products and systems. Rather than evaluating nudges solely by their effects, we examine the embedded design and behavior. Using a structured classification framework, we differentiate four key types of nudges - Reflective-Decisive (RD), Reflective-Non-Decisive (RND), Non-Reflective-Decisive (NRD), and Non-Reflective-Non-Decisive (NRND) - and how humans use their thought processes to interact with each.

A nudge’s effectiveness is closely tied to how it aligns with the user and their choices. For instance, RD/T1T nudges encourage intentional decision-making and are critical to the user’s final choice, whereas NRND/T2NT nudges operate passively, without requiring a user’s engagement. This view enables organizations to design and deploy interventions alongside features to determine what is a better choice, enhancing both the behavioral impact and user experience.

By mapping nudges to their underlying design traits, businesses, and products, teams can more accurately forecast user responses and provide better outcomes. This approach offers a scalable model for product development, service design, and digital transformation initiatives.

This article was written by Roque Martinez, CTO of Frontier Foundry. Visit his LinkedIn here.

To stay up to date with our work, visit our website, or follow us on LinkedIn, X, and Bluesky. To learn more about the services we offer, please visit our product page.

References

Abdukadirov, S. (2016). Nudge Theory in Action : Behavioral Design in Policy and Markets (1st 2016. ed.). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31319-1

Anders Haug, J. B. (2014). A Framework of Ethical Nudges in the Design of Consumer Goods. Design Research Society DRS2014: Design’s Big Debates, 16-19. (https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drsconference-papers/drs2014/researchpapers/120)

Dellaert, B. G. C., Johnson, E. J., Duncan, S., & Baker, T. (2024). Choice Architecture for Healthier Insurance Decisions: Ordering and Partitioning Together Can Improve Consumer Choice. Journal of marketing, 88(1), 15-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429221119086

Drouin, O. (2023). Public acceptability of nudges targeting parents and children to improve children’s health outcomes: results from an online experiment. Behavioural Public Policy, 7(2), 470-487. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.13

Hansen, P., & Jespersen, A. (2013). Nudge and the Manipulation of Choice: A Framework for the Responsible Use of the Nudge Approach to Behaviour Change in Public Policy. European Journal of Risk Regulation.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.